North American Green Frog

Lithobates clamitans

Common Name: |

North American Green Frog |

Scientific Name: |

Lithobates clamitans |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Lithobates is Greek, Litho means "A stone", bates means "One that walks or haunts" |

Species: |

clamitans is Latin meaning "loud calling" |

Average Length: |

2.3 - 3.5 in. (5.7 - 9 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

|

Record length: |

4.3 in. (10.8 cm) |

Physical Description - Adults of this species generally range from 54 to 90 mm (2 to 3.5 in) in length. Dorsal coloration is highly variable but is typically green or brown with obscure brown spots or blotches. The ventrum is white and occasionally marked with dark spots particularly in the young. Blue-colored specimens have been found; these specimens lack yellow pigment. Throats of males may be bright yellow. Males also possess a larger tympanum and stouter forelegs and thumbs than females. In both sexes the dorsal lateral fold only extends to the middle of the back; it does not reach the groin. Young specimens typically have small dark dorsal spots and mottled ventrum. Tadpoles are 74 to 100 mm in length with a body to tail ratio of 1:1.8. Tail fin is darkly mottled. Body may have a few dark spots. The intestinal coil is not visible. The oral disc is strongly emarginated with large, flattened, heavily pigmented papillae. The upper jaw is slightly cuspate with labial tooth rows 2/3.

Historical versus Current Distribution - The range of North American Green Frogs (Lithobates clamitans) encompasses most of the eastern United States, from the Canadian border south to the Gulf of Mexico. Green frogs occur almost everywhere east of a line drawn from central Minnesota south through central Iowa, southeast through Missouri (excluding the northwestern corner), and south through central Oklahoma and eastern Texas (Conant and Collins, 1998). North American Green Frogs are absent from the southern half of Florida, from much of central Illinois (a distribution Smith [1961] termed puzzling), and from half a dozen scattered counties in north-central Arkansas. Geographic isolates occur in western Iowa, northern Utah, and in several locations in the state of Washington (Stebbins, 1985; Leonard et al., 1993). North American Green Frogs have been introduced in the states of Washington and Utah, and in western Iowa.

Historical versus Current Abundance - Little data are available, although North American Green Frogs are generally considered common or abundant (Smith, 1961; Mount, 1975; Vogt, 1981; Dundee and Rossman, 1989; Klemens, 1993; Hunter et al., 1999; Mitchell and Reay, 1999. Populations have undoubtedly been affected by shoreline development throughout much of the range. Lannoo et al. (1998) documented a mass mortality event apparently associated with a cold snap in northern Wisconsin. Ouellet et al. (1997a) documented North American Green Frog malformations from agriculturally impacted sites in Québec.

Breeding - Reproduction is aquatic.

Breeding migrations - Adults generally breed in the same lakes and permanent wetlands they inhabit during the non-breeding season, so migrations to breeding sites are rare. Males remain at the breeding sites for ≤ 2 mo, but females usually only stay for about 1 wk when they mate and deposit eggs (Martof, 1953).

The breeding period is extended, from April through the summer, depending on latitude. Examples of breeding times include early May to early July in Ohio (Walker, 1946), Indiana (Minton, 1972), Connecticut (Klemens, 1993), Maryland, and Delaware (Lee, 1973); May–August in Kentucky (Barbour, 1971), Maine (Hunter et al., 1992; Hunter et al., 1999), and Minnesota (Breckenridge, 1944); May–September in Illinois (Phillips et al., 1999); April to late June in Kansas (Collins, 1993); April–August or September in Alabama (Mount, 1975) and Missouri (Johnson, 1987); and March–September in Louisiana (Dundee and Rossman, 1989). In Michigan, North American Green Frogs breed from mid May to well into the summer (Harding and Holman, 1999). Wright and Wright (1949) note that green frogs breed late in the South. In West Virginia, North American Green Frogs breed from mid April to July in the South and June–August in the North (Pauley and Barron, 1995; Rogers, 1999).

Breeding habitat - Adult North American Green Frogs inhabit shorelines of lakes and permanent wetlands such as ponds, bogs, fens, marshes, swamps, and streams.

Egg deposition sites - Eggs are deposited in shallow water among emergent vegetation (sedges, cattails, rushes) along the shores of lakes and permanent wetlands. Eggs are in a foamy surface film (plinth) that is usually < 30 cm in diameter (Walker, 1946; Green and Pauley, 1987).

Clutch size - Clutch sizes vary with the size of females, from 1,000 to nearly 7,000 eggs (Pope, 1944; Wright and Wright, 1949; Minton, 1972; Wells, 1976; Barbour, 1971; Dundee and Rossman, 1989; Oldfield and Moriarty, 1994; Hunter et al., 1999). Eggs masses of females breeding simultaneously can coalesce into a single mass (Wright and Wright, 1949). Some females are known to breed twice annually in the area around Ithaca, New York (Wells, 1976; Martof, 1956b). Second clutches number between 1,000–1,500 eggs.

Eggs are black above and white below and measure about 1.5 mm in diameter (Wright and Wright, 1949; Green and Pauley, 1987; Rogers, 1999). Hatching occurs a few days after deposition (Walker, 1946; Smith, 1961; Green and Pauley, 1987; Johnson, 1987; Harding and Holman, 1999; Hunter et al., 1999). Hatchlings range in size from 10–12 mm TL in Indiana (Minton, 1972) and 9.8–16 mm in West Virginia (Rogers, 1999).

Altig & McDiarmid 2015 - Classification and Description:

- Eastern Film

- Arrangement 3 - Film diameter greater than 200 mm; ovum black and jelly diameter not large relative to ovum size.

- Sub-arrangement B - Eggs deposited in larger, often swampy, nonflowing water; Ovum Diameter 1.2-1.8 mm; Egg Diameter 2.8 -4.0 mm; Z jelly layers; clutch 1000-5000.

- Arrangement 3 - Film diameter greater than 200 mm; ovum black and jelly diameter not large relative to ovum size.

Tadpoles:

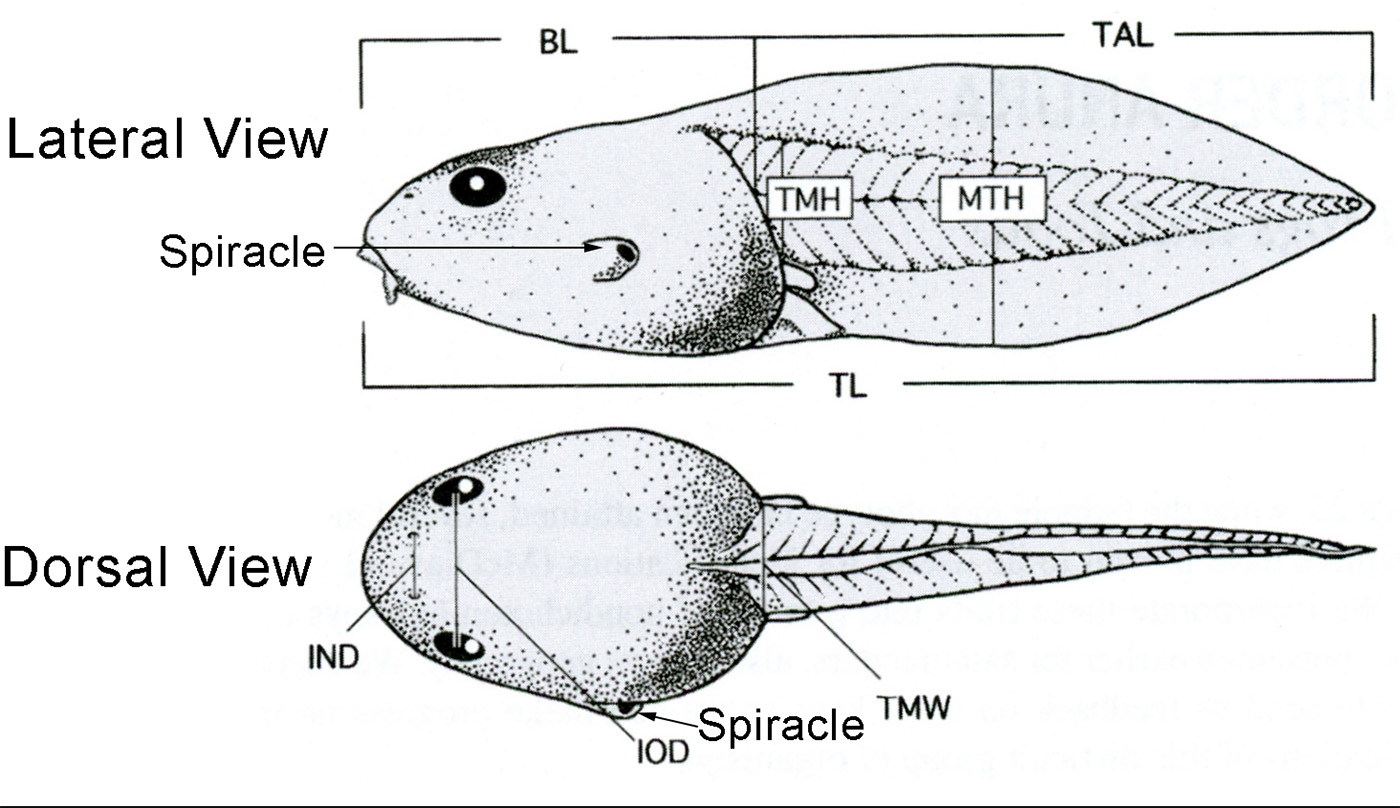

| Lateral View | Dorsal View |

|---|---|

| BL = Body Length | IND = Internarial Distance |

| MTH = Maximum Tail Height | IOD = Interorbital Distance |

| TAL = Tail Length | TMW = Tail Muscle Width |

| TL = Total Length | |

| TMH = Tail Muscle Height |

Length of larval stage - Ryan (1953), Whitaker (1961), and Wells (1976) report metamorphosing young from the end of June to mid July in the area around Ithaca, New York. Larvae metamorphose from April–September in Kentucky (Barbour, 1971), and from early June to late September in Connecticut (Klemens, 1993). In northern West Virginia, Rogers (1999) found newly transformed young from June–October, with a peak in numbers in August. In Kansas, where tadpoles do not typically overwinter, the larval period is about 3 mo (Collins, 1993).

Tadpoles overwinter in many areas throughout their range (Babbitt, 1937; Breckenridge, 1944; Walker, 1946; Wright and Wright, 1949; Smith, 1961; Minton, 1972; Mitchell and Anderson, 1994; Phillips et al., 1999; Rogers, 1999). In a laboratory experiment, Ting (1951) determined that tadpoles from early breeders should be able to metamorphose during the same year, but those from late broods may not transform until the next year (see also Vogt, 1981).

Larvae Food - Tadpoles feed during the day on a variety of organic debris (Jenssen, 1967; Warkentin, 1992a,b). Werner and McPeek (1994) reported that they are mostly benthic feeders and feed primarily on algae, especially diatoms, but will take entomostracans and fungi.

Cover - Both large and small North American Green Frog tadpoles seek cover in vegetation during the day (Warkentin, 1992a,b). They also have been found under stones, logs, and bark near water (Minton, 1972).

Larval polymorphisms - Larvae that have overwintered will prey on Wood Frog eggs and larvae (Wegmann, 1997; T.K.P., personal observations).

Features of metamorphosis - Tadpoles are 60–80 mm TL at metamorphosis (Minton, 1972; Johnson, 1977; Dundee and Rossman, 1989; Rogers, 1999); following tail resorption, their sizes range from 21–38 mm. Smaller sizes have been reported in the southern part of the range (Wright and Wright, 1949; Martof, 1956b; Minton, 1972). Metamorphosing frogs are found throughout the summer and early fall in Indiana (Minton, 1972) and West Virginia (Rogers, 1999). First-year frogs will grow about 34 mm (Minton, 1972).

Post-metamorphic migrations - Juveniles will disperse into woods and meadows during rainy weather (Harding and Holman, 1999). Subadults may move from 200 m–4.8 km (3 mi) during their first season following transformation (Schroeder, 1968b).

Juvenile Habitat - Smaller North American Green Frogs are generally found in less-dense vegetation than are adults (Martof, 1953). They hide and feed along the margins of ponds and streams (Hunter et al., 1999) and are commonly found in road rut ponds (T.K.P., personal observation). Vogt (1981) reported that froglets are terrestrial and spend their first summer on land in Wisconsin.

Adult Habitat - North American Green Frogs are found in most permanent aquatic habitats. Habitats include shorelines of lakes and permanent wetlands, in areas where emergent vegetation such as sedges, cattails, and rushes predominate (Whitaker, 1961; Collins, 1993), and in marshes, swamps, streams, springs, and quarry and farm ponds (Walker, 1946; Minton, 1972; Mount, 1975; Green and Pauley, 1987; Johnson, 1987; Dundee and Rossman, 1989; Collins, 1993; Klemens, 1993; Harding and Holman, 1999; Hunter et al., 1999; Phillips et al., 1999). Smith (1961) observed that in northern Illinois, North American Green Frogs occur in a variety of habitats, while in southern Illinois, they are restricted to clear streams associated with rock outcrops. Minton (1972) found that adults rarely go more than 1 m from water except on rainy nights.

North American Green Frogs have been found associated with the mouths of caves (Black, 1973; Trauth and McAllister, 1983; Garton et al., 1993).

Home Range Size - Adults have an average home range of 62 m2 (Hamilton, 1948). In Michigan, Martof (1953) found that North American Green Frogs have a terrestrial home range of about 20–200 m2 (average of about 60 m2) that they leave during the breeding season and return to after breeding.

Territories - During their prolonged breeding season, males are territorial, with an average residency of about 1 wk (with a range of < 1–7 wk). Males inhabit their territories throughout most of the evening during breeding and defend these territories using vocalizations, posturing, and physical combat (Jenssen and Preston, 1968; Wells, 1977, 1978; Ramer et al., 1983; Given, 1990). Schroeder (1968a) observed two males in combat over an apparent breeding site. Green frogs have been shown to use advertisement calls to assess the size of opponents during aggressive encounters (Bee et al., 1999).

Territories are usually centered around clumps of rushes (Scirpus sp.) or sedges (Carex sp.), artificial shelters, and occasionally abandoned muskrat tunnels (Wells, 1977b). Territory size is dependent on cover density. In dense vegetation, males may be only 1.0 to 1.5 m apart. In more open shorelines, males may be spaced 4.0 to 6.0 m apart (Wells, 1977b).

During non-breeding, Wright and Wright (1949) note that North American Green Frogs are solitary. Further, Martof (1956b) showed that most males are solitary during the breeding season, but may later congregate in large groups (called congresses).

Aestivation/Avoiding Dessication - Minton (1972) notes that under dry conditions adults will aggregate around springs or watering holes.

Seasonal Migrations - North American Green Frogs probably do not migrate en masse to breeding sites. Lamoureux and Madison (1999) tracked 23 North American Green Frogs and found that they made extensive movements in late fall away from summer breeding ponds to areas of flowing water in streams and seeps. They suggested that flowing water is used because it remains unfrozen and provides adequate oxygen.

Torpor (Hibernation) - North American Green Frog tadpoles will typically, but not always, overwinter for 1 yr prior to metamorphosing the following spring (Martof, 1952; Richmond, 1964; Vogt, 1981). While overwintering, and despite cold temperatures, tadpoles remain active and likely feed (Getz, 1958). Tadpoles probably remain active and grow during the winter in Louisiana but do not transform until warm weather (Dundee and Rossman, 1989). In Maine, they remain under silt and dead vegetation during the winter (Hunter et al., 1999). Both tadpoles and adults require aquatic sites that do not completely freeze and that also maintain enough oxygen during the winter (Oldfield and Moriarty, 1994).

North American Green Frog adults typically overwinter in water (Dickerson, 1906; Walker, 1946; Pope, 1947; Wright and Wright, 1949; Harding and Holman, 1999) but will occasionally overwinter on land (Bohnsack, 1951). The frog followed by Bohnsack (1951) was found beneath 5 cm (2 in) of compact leaf litter in an oak-hickory forest near Pickney, Michigan. Lannoo et al. (1998) cites an instance where a large number (25, including 4 gravid females) of North American Green Frogs were caught on land near a wetland during a cold snap in northern Wisconsin. Minton (1972) notes that adults near Indianapolis, Indiana, seek cover from early December to early March and that juveniles emerge earlier in the season than do adults. In Maine, North American Green Frogs hibernate either underwater or underground from October–March (Hunter et al., 1999). In Ohio, several hibernating individuals have been found in springs and in masses of leaves and aquatic vegetation on the bottom of small ponds (Walker, 1946).

Interspecific Associations/Exclusions - In New Jersey, North American Green Frogs and Carpenter Frogs (L. virgatipes) breed in the same lakes and have overlapping breeding seasons, calling site preferences, and vocal repertoires; they also exhibit generally similar territorial behaviors (Wells, 1977, 1978; Given, 1987, 1990). Nevertheless, Given (1990) shows that Carpenter Frogs are less territorial but more aggressive than are North American Green Frogs in these breeding aggregations. Working in West Virginia, Pauley and Barron (1995) observed that North American Green Frogs breed in the same ponds as Leopard Frogs, Pickerel Frogs, and Bullfrogs, but only American Bullfrogs have an overlapping breeding season with North American Green Frogs. In northern Minnesota, North American Green Frogs commonly occur with Mink Frogs (Lithobates septentrionalis; Oldfield and Moriarty, 1994). However, Mink Frogs usually inhabit floating vegetation in deeper water while North American Green Frogs are found along the edges of the water. This habitat partitioning reduces interspecific competition for food (Fleming, 1976). Minton (1972) reports two cases of male North American Green Frogs in amplexus with leopard frogs, once with a male and once with a female.

Trauth and McAllister (1983) reported a male using a cave associated with American Bullfrogs, Long-tailed Salamanders (Eurycea longicauda), Cave Salamanders (E. lucifuga), Many-ribbed Salamanders (E. multiplicata), and Northern Slimy Salamanders (Plethodon glutinosus).

Age/Size at Reproductive Maturity - Females are slightly larger than males (Smith, 1961). In Indiana, males range from 60–84.5 mm TL, females from 64–88 mm (Minton, 1972); in Ohio, females range from 72–92 mm, males from 69–90 mm (Walker, 1946); and in Connecticut, females range from 52–84 mm, males from 52–94 mm (Klemens, 1993). Males in the South are smaller than in the North (Wright and Wright, 1949). Minton (1972) and Hunter et al. (1999) note that North American Green Frogs become sexually mature about 1 yr after metamorphosis. In Maine, females reach sexual maturity at 65–75 mm and males at 60–65 mm (Hunter et al., 1999). Four to five years are required to reach adult size in Michigan (Minton, 1972; Harding and Holman, 1999).

Longevity - Cortwright (1998) estimated that at least two population turnovers occurred during a 10–11-yr study in south-central Indiana.

Feeding Behavior - As pointed out by Forstner et al. (1998), frogs, including North American Green Frogs, are opportunistic feeders, choosing and eating prey from an assortment of moving animals that are large enough to detect and small enough to swallow. Thus, prey choice reflects both habitat and availability (Jenssen and Klimstra, 1966; Hedeen, 1972b; Kramek, 1972; Stewart and Sandison, 1972), although both species and individuals within species can specialize (Sweetman, 1944; Forstner et al., 1998).

North American Green Frog adults are "sit-and-wait" predators (Hamilton, 1948) and will feed both day and night (Minton, 1972). Several authors, including Hamilton (1948), Whitaker (1961), Stewart and Sandison (1972), and Forstner et al. (1998) provide a list of North American Green Frog prey that includes invertebrates such as annelids, mollusks, millipedes, centipedes, crustaceans, and arachnids; insects such as coleopterans, dipterans, ephemeropterans, hemipterans, lepidopterans, odonates, orthopterans, and trichopterans; and vertebrates such as fishes and other frogs; vegetable matter; and shed skins. Further, Forstner et al., 1998 and other authors have shown that food habits vary over the summer as prey availability changes.

Predators - Martof (1956b) reports that all stages of the life history of North American Green Frogs have several predators. Eggs are eaten by turtles. Tadpoles are eaten by larvae of diving beetles and whirligig beetles, nymphs of dragonflies and giant water bugs, and adults of giant water bugs, water scorpions, and back swimmers. North American Green Frogs are preyed upon by ducks, herons, bitterns, rails, northern harriers, and crows. Large North American Green Frogs will take smaller ones and American Bullfrogs take almost all sizes of North American Green Frogs. North American Green Frogs showed a fourfold increase in 4 yr after Bullfrogs disappeared in Point Pelee National Park in Ontario (Hecnar and M’Closkey, 1997). Klemens (1993) reports North American Green Frogs in stomachs of watersnakes and gartersnakes. People use North American Green Frogs for food and for sport (Hamilton, 1948).

Anti-Predator Mechanisms - Startled North American Green Frogs will emit a squawk when they jump (Smith, 1961).

Diseases - Mikaelian et al. (2000) document myositis associated with an infection from Ichthyophonus-like protists from animals collected in Québec, Canada. Other reported diseases include frog erythrocytic virus (Faeh et al., 1998).

Parasites - Trematodes reported include Halipegus occidualis (Goater et al., 1990; Wetzel and Esch, 1996; Zelmer et al., 1999) and H. eccentricus (Goater et al., 1990; Wetzel and Esch, 1996). Other parasites reported include digeneans, cestodes, acanthocephalans, and Glypthelmins quieta (McAlpine, 1997c).

Conservation - North American Green Frogs are relatively common throughout most of their range. They are classified as a Game Species in some states (e.g., Missouri, Mississippi, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania), thereby providing them with protection in terms of hunting season and bag limits (Levell, 1997). In Kansas, North American Green Frogs are protected by state law (Collins, 1993) and are listed as a Threatened species (Levell, 1997). Populations have undoubtedly been lost as shorelines have been developed for recreational, business, and domestic uses. North American Green Frogs fall victim to vehicular traffic (Ashley and Robinson, 1996).

References for Life History

- Altig, Ronald & McDiarmid, Roy W. 2015. Handbook of Larval Amphibians of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. 341 pages.

- AmphibiaWeb. 2020. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA.

- Conant, Roger and, Collins, John T., 2016, Peterson Field Guide: Reptiles and Amphibians, Eastern and Central North America, 494 pgs., Houghton Mifflin Company., New York

- Duellman, William E. and, Trueb, Linda, 1986, Biology of Amphibians, 671 pgs., The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

- Martof, B.S., Palmer, W.M., Bailey, J.R., Harrison, III J.R., 1980, Amphibians and Reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia, 264 pgs., UNC Press, Chapel Hill, NC

- Wilson, L.A., 1995, Land manager's guide to the amphibians and reptiles of the South, 360 pp. pgs., The Nature Conservancy, Southeastern Region, Chapel Hill, NC

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence

Accomack

Albemarle

Alleghany

Amelia

Amherst

Appomattox

Arlington

Augusta

Bath

Bedford

Botetourt

Brunswick

Buchanan

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Carroll

Charles City

Chesterfield

Clarke

Culpeper

Cumberland

Dickenson

Dinwiddie

Essex

Fairfax

Fauquier

Floyd

Fluvanna

Franklin

Frederick

Giles

Gloucester

Goochland

Grayson

Greene

Greensville

Halifax

Hanover

Henrico

Henry

Highland

Isle of Wight

James City

King and Queen

King George

King William

Lancaster

Lee

Loudoun

Louisa

Lunenburg

Madison

Mathews

Mecklenburg

Middlesex

Montgomery

Nelson

New Kent

Northampton

Northumberland

Nottoway

Orange

Page

Patrick

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Pulaski

Rappahannock

Richmond

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Rockingham

Russell

Scott

Shenandoah

Smyth

Southampton

Spotsylvania

Stafford

Surry

Sussex

Tazewell

Warren

Washington

Westmoreland

Wise

Wythe

York

CITIES

Alexandria

Bristol

Charlottesville

Chesapeake

Colonial Heights

Fairfax

Franklin

Hampton

Hopewell

Lynchburg

Newport News

Petersburg

Poquoson

Radford

Roanoke

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Williamsburg

Winchester

Verified in 92 counties and 19 cities.

U.S. Range