Family Viperidae: This family comprises 150+ species

in 20+ genera distributed on all continents except Antarctica and Australia (Zug, 1993).

Most are heavy-bodied snakes with a distinct head and vertical pupils in the eye. Vipers

possess a pair of hollow

fangs, one on each of the two maxilla bones located beneath the nostrils. The bones and

fangs rotate from a resting position along the roof of the mouth to an erect position by the

mechanical action of lowering the lower jaw. These fangs provide the functional means to

inject modified saliva (venom) deep into prey. Venom glands lie behind the eyes under the

masseter muscle and each is connected to the fang by a hollow duct. Vipers regulate the

amount of venom injected by their control over the masseter muscle. Venom, and the means to

inject it, evolved for the purpose of prey capture, but it is sometimes used as a defensive

measure.

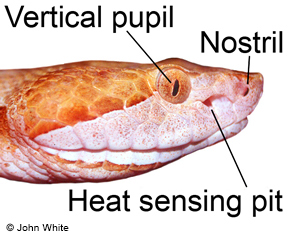

The majority of the species in this family are pit vipers (120+ species); the remaining 50

or so species are true vipers. Each species of pit viper possesses a heat-sensing pit

located between the eye and nostril that is used to aid in prey location. This group is

often classified in the subfamily Crotalinae, although some taxonomists refer them to

full

family status, the Crotalidae. The pit organ contains heat-sensitive cells that are

responsive to changes in temperature of 0.001°C (Halliday and Adler, 1986). This mechanism

probably evolved to allow prey capture in dark spaces, like rodent burrows. A pit viper can

detect the presence of a rodent prey and determine its relative size and distance in total

darkness.

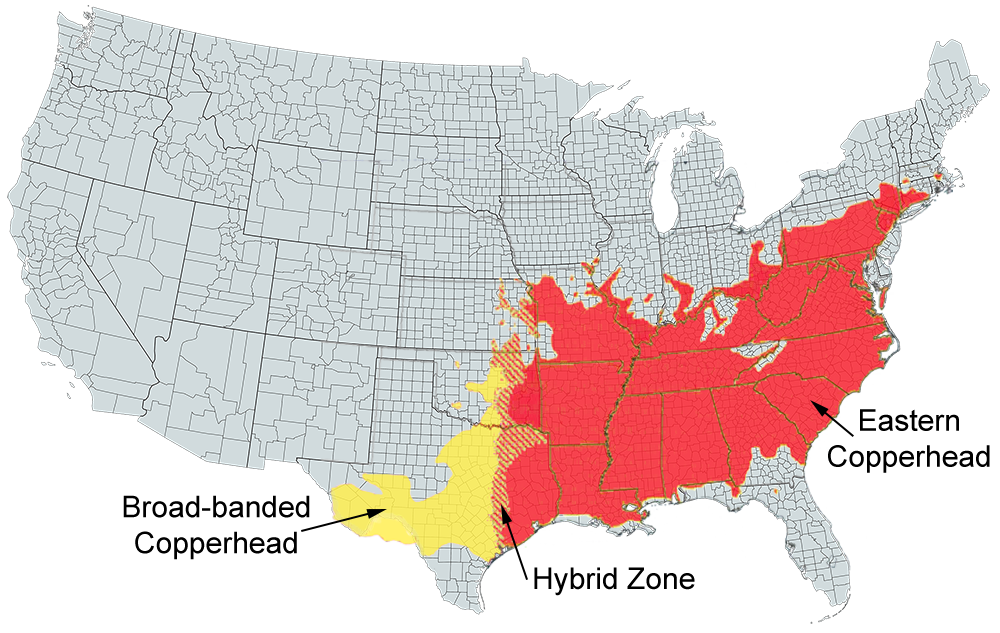

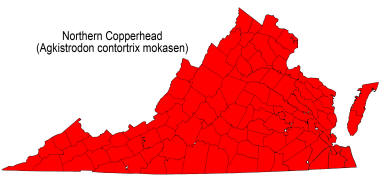

The family Viperidae is represented in Virginia by only three species of pit vipers: the

Timber Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus), the Eastern Copperhead (Agkistrodon

contortrix) and the Northern Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus).

Systematics: Originally described as Boa

contortrix

by Carolus Linnaeus in 1766, based on a specimen sent to him by Alexander Garden from

"Carolina." Schmidt (1953) restricted the type locality to

Charleston, South Carolina. The genus Agkistrodon was first used for this species by

Palisot

de Beauvois in 1799 (Gloyd and Conant, 1990). Early authors interpreted the spelling of the

genus to be either Agkistrodon, following Baird and Girard (1853) and Stejneger and

Barbour

(1917, 1923, 1933, 1939, 1943), or Ancistrodon (Wagler, 1830; Cope, 1860), and thus

the

generic name flip-flopped between these two spellings for well over the last century. In the

Virginia literature, Ancistrodon was used by Cope (1900), Dunn (1915d), Schmidt

(1953), Wood

(1954a), Martin and Wood (1955), Goodwin and Wood (1956), Hutchison (1956), and Reed (1957a,

1957b). Agkistrodon was used by Hay (1902), Dunn (1915a, 1915c), Werler and McCallion

(1951), Conant (1958,1975), Burger (1958), Musick (1972), Mitchell (1974b, 1981a), Martof et

al. (1980), and others. Klauber (1956) showed that Agkistrodon was the most

appropriate

spelling based on the Law of Priority. Baird and Girard (1853) first assigned the specific

name contortrix to Agkistrodon, and numerous authors in the Virginia

literature (noted

above) used the combination Agkistrodon (or Ancistrodon) contortrix.

Description: A medium-sized, heavily bodied snake

reaching a maximum total length of 1,346 mm (53.0 inches) (Gloyd and

Conant, 1990). In Virginia, maximum known snout-vent length (SVL) is 1,094 mm (43.1 inches)

and maximum total length is 1,219 mm (48.0 inches). Tail length/total length in the Virginia

sample was 10.0-16.7% (ave. = 13.3 ± 1.3, n = 185).

Scutellation: Ventrals 140-157 (ave. = 147.9 ±

2.5, n = 214); subcaudals 38-53 (ave. = 45.3 ± 1.5, n = 197) and single, except for 0-17

divided subcaudal scales (ave. = 6.8 ± 4.4, n = 183) near tip of tail; ventrals +

subcaudals 183-203 (ave. = 193.2 ± 3.7, n = 197); dorsal scales strongly keeled, scale rows

23 at midbody; anal plate single; infralabials 10/10 (41.0%, n = 178), 9/9 (27.5%), or

combinations of 8-11 (31.5%); supralabials 8/8 (56.2%, n = 178), 7/7 (14.6%), 7/8 (25.8%),

or combinations of 6-9 (3.4%); loreal scale present;

preoculars 2-3; 4-5 small scales separating eye from supralabials and temporals; temporal

scales variable, generally combinations of 4-7 + 5-7 on both sides.

Coloration and Pattern: Dorsum of body and tail

pinkish tan to dark brown to nearly black with a series of 10-18 (ave. = 14.5 ± 1.5, n =

221) hourglass-shaped crossbands; crossbands chestnut to dark brown, narrow (2-5 scales at

middorsal) in middle and wide laterally; 0-8 bands (ave. = 1.4 ± 1.5, n = 211) may not be

connected at middorsal line and some halves may lack partners altogether; crossbands start

above scale row 1 on each side and are lighter in centers on side and darker at middorsal

area; small, dark-brown blotches-2 scales in diameter or less may be present between

crossbands; most dorsal scales sprinkled with black flecks, which in some snakes may be

quite intense; ventrolateral black spots, below and between crossbands, are all of nearly

equal intensity, except toward tail; venter cream with variable amounts of black flecking

and black smudges; dorsum of head tan to brick red (resembling red Piedmont clay) to brown

and separated from white to cream labial region by a thin, dark-brown line; usually 1 tiny,

dark-brown spot in each of 2 parietal scales on center of dorsum of head; chin cream,

usually without black flecking. The head is somewhat triangular and distinct from the narrow

neck. The dorsum of the head is flat.

Sexual Dimorphism: Adult males reached a larger

average SVL (732.7 ± 153.4 mm, 500-1,094, n = 99) than females (597.8 ± 92.6 mm, 380-952, n

= 80) and reached a longer total length (1,219 mm; females 1,083 mm). Sexual dimorphism

index

was -0.23. The variation in tail length/total length was nearly identical for both sexes

(males 10.0-16.5%, ave. = 13.3 ± 1.3, n = 102; females 10.6-16.7%, ave. = 13.3 ± 1.2, n =

78). Average body mass in adult males (272.9 ± 136.4 g, 91-525, n = 15) was greater than

that in adult females (178.1 ±

69.6 g, 103-318, n = 7).

The average number of ventral scales was similar between sexes (males 147.8 ± 2.2, 140-154, n

= 118; females 148.1 ± 2.6, 141-157, n = 91), as was the average number of body crossbands

(males 14.5 ± 1.5, 11-18, n = 121; females 14.6 ± 1.5, 10-18, n = 95). The average number of

subcaudals was slightly higher in males (46.4 ± 2.5, 38-53, n = 108) than in females (44.0 ±

2.3, 38-52, n = 84). A similar pattern was expressed in the average number of ventrals +

subcaudals (males 194.4 ± 3.3, 185-201, n = 108; females 192.0 ± 3.7, 183-203, n = 84).

There are no apparent sexual differences in color or pattern.

Juveniles: Juveniles are colored and patterned as

adults, with the notable exception that the tip of the tail (about 25-30% of its length) is

sulfur yellow. Juveniles lack the black flecking seen in adults; it appears with

age. Neonates had a SVL of 170-205 mm (ave. = 196.5 ± 8.7, n = 17), a total length of

204-243 mm (ave. = 233.2 ± 8.7, n = 16), and an average body mass of 7.0 g (mean for one

litter). Gloyd and Conant (1990) reported that newborn A. contortrix had a total

length of

190-280 mm and weighed 7.2-9.4 g.

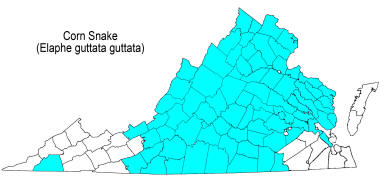

Confusing Species: Many people in Virginia call

almost every snake with a pattern an Eastern Copperhead. Corn Snakes (Pantherophis

guttatus) have a series

of chestnut-brown blotches, each surrounded by black, along the dorsum; a gray to

reddish-brown background; a conspicuous eye-jaw stripe; and a black-and-white checkerboard

venter. Eastern Milk Snakes (Lampropeltis triangulum) have brownish blotches on a

gray to gray-brown

background and either a black-and-white checkerboard pattern or extensions of the dorsal

pattern on the venter. Juvenile Eastern Ratsnakes (Pantherophis alleghaniensis),

often killed for

Eastern Copperheads, have a series of dark-brown blotches on a grayish-white background and

a dark

eye-jaw stripe. The Northern Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus) is darker and has

broad, dark-olive to black crossbands on a

yellowish to olive background, a dark-olive to yellowish-olive head, and a black tail.

Juvenile Northern Cottonmouths have the yellow tail tip and broad crossbands on a pinkish to

brownish

background.

Geographic Variation: The average number of ventral

scales (males and females combined) varied from 144.2 ± 2.7 (141-148, n = 6) in the

Appalachian Plateau to 148.5 ± 2.7 (144-153, n = 19) in the lower Piedmont, except for the

sample from the southern Blue

Ridge Plateau, which averaged 150.8 ± 3.1 (148-156, n = 5) . The average number of

subcaudals (entire + paired) ranged from 44.2 ± 3.7 (38-49, n =

17) in the lower Ridge and Valley region to 45.8 ± 2.9 (42-53, n = 42) in the southern

Coastal Plain. The number of divided (paired) subcaudals varied from a low of 5.0 ± 1.6

(3-7, n = 4) in the southern Blue Ridge Plateau to a high of 8.8 ± 2.7 (6-13, n =

6) in the Ridge and Valley north of the New River and 8.8 ± 5.3 (1-15, n = 6) in the

Appalachian Plateau.

The average number of body crossbands varied from 14.0 ± 1.1 (12-17, n = 44) in the southern

Coastal Plain to 15.7 ± 0.5 (15-16, n = 6) in the Appalachian Plateau. Individuals of Agkistrodon

contortrix with 1-3 broken crossbands are common

throughout Virginia. Fourteen specimens with 4-6 broken crossbands were collected from the

lower Coastal Plain, the upper and lower Piedmont, and in Shenandoah National Park in the

Blue Ridge Mountains. One A. contortrix specimen from Lunenburg County, in the lower

Piedmont, had 8 broken crossbands, and one from Botetourt County, in the northern Blue Ridge

Mountains, had 7. The width of the midbody

crossband at the middorsal line varies from 2 to 5 scales; widths of 1 or 6 are rare. Counts

of 2-3.5 are common throughout Virginia. The higher counts of 4-5 are commonly found in

snakes from the Blue Ridge Mountains westward; counts of 2-4 have been recorded for snakes

from southeastern Virginia.

Geographic variation in Virginia A. contortrix is expressed primarily in body color

and

pattern. Snakes from southeastern Virginia have brown to dark-tan crossbands on a light-tan

to pinkish background, and reddish-tan heads; those from the Piedmont have dark-brown or

chestnut crossbands on a reddish-brown to grayish-brown background, and reddish heads (much

like the color of Piedmont clay); and those from the mountains and Ridge and Valley have

dark-brown or chestnut crossbands on a brown to grayish-brown body, with heads of various

shades of brown. Snakes from the extreme southwestern region of Virginia and many snakes

from the mountains possess considerable black flecking over the body, producing in some

cases a very dark snake. These are general differences, as individuals in any region may

show extremes in color. Individual specimens of Agkistrodon contortrix from the

Piedmont and

mountains often exhibit a series of lateral brown spots alternating with the dorsal

crossbands. Snakes in southeastern Virginia usually do not possess this character.

Biology: Eastern Copperheads are terrestrial snakes

inhabiting a wide array of habitats. They are found in hardwood and mixed hardwood-pine

forests, pine woods, abandoned fields in various stages of succession, high ground in swamps

and marshes, forest-field ecotones, hedge rows, suburban woodlots, ravines along creeks in

agricultural and urban areas, upland rocky areas, rock walls and woodpiles, and forested

dunes near beaches, as well as around barns and houses (especially dilapidated ones) in

agricultural areas. Musick (1972) noted that blueberry thickets are favored habitat. In

Pennsylvania, Reinert (1984a, 1984b) found that A. contortrix utilized relatively

open areas

with higher rock density and less surface vegetation than the sympatric Timber Rattlesnake

(Crotalus horridus). This probably pertains to upland Virginia habitats as well. I

have

found them coiled under vegetation in orchards and on farms. Habitat requirements appear to

be sunlit areas with sources of prey (see below), and year-round shelter. Such places are

often found near human

habitation, and A. contortrix will take advantage of these situations. Eastern

Copperheads will

seldom climb high into vegetation but will swim when necessary.

Agkistrodon contortrix is diurnal and nocturnal during warm weather (generally May

through

September), depending on the temperature, and is primarily diurnal in the cooler seasons.

Movement is stimulated by rains and the urge to mate and seek food. The normal seasonal

activity period is 9 April through 30 October (museum records). Clifford (1976) recorded

active snakes from May to October in Amelia County. Wood (1954a) reported that individuals

of A. contortrix were seen from 16 April to 12 December in Shenandoah National Park,

but

that it was uncommon to find them earlier than May or later than September. Elevation

influences the length of the activity season. Eastern Copperheads often overwinter in

aggregations

in dens, sometimes shared with Crotalus horridus (Wood, 1954a) or Coluber

constrictor (C.

H. Ernst, pers. comm.), in the mountains, but in small numbers or singly in the Piedmont,

Coastal Plain, and low-elevation valleys in the Ridge and Valley region.

Eastern Copperheads are predators of many types of prey. What they eat depends on the size of

the

snake and the types of prey available. Juveniles consume more invertebrates than adults,

whereas adults eat more small mammals. In their study in the George Washington National

Forest, Uhler et al. (1939) found the following prey in 72 specimens: meadow voles (Microtus

pennsylvanicus), woodland voles (Microtus pinetorum), southern red-backed

voles

(Clethrionomys gapperi), southern bog lemmings (Synaptomys cooperi),

white-footed mice

(Peromyscus leucopus), jumping mice (Zapus or Napaeozapus), chipmunks (Tamias

striatus),

unidentified squirrels, northern short-tailed shrews (Blarina brevicauda), least

shrews

(Cryptotis parva), masked shrews (Sorex cinereus), hairy-tailed moles

(Parascalops breweri), ruby-throated hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris), an

unidentified

warbler (Dendroica spp.), an unidentified passerine bird, Slimy Salamanders (Plethodon

glutinosus = cylindraceus), Red-backed Salamanders (Plethodon cinereus), Red

Salamanders

(Pseudotriton ruber), an unidentified frog (Lithobates spp.), Fence Lizards

(Sceloporus undulatus),

Eastern Wormsnakes (Carphophis amoenus), moth caterpillars, and cicada nymphs. De

Rageot

(1957) reported a Dismal Swamp short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda telmalestes)

from an

Eastern Copperhead collected in the Dismal Swamp. I found a star-nosed mole (Condylura

cristata) in

a specimen from Giles County. To this list C. H. Ernst (pers. comm.) added skinks (Plestiodon

spp.) and Eastern Garter Snakes (Thannophis sirtalis). Predators of Eastern

Copperheads are not

well known. Megonigal (1985) reported the predation of a Dismal Swamp adult by an Eastern

Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula). W. H. Martin (pers. comm.) observed a broad-winged

hawk

(Buteo platypterus) catching an Eastern Copperhead by a rock wall along the Skyline

Drive in

Rockingham County. Gloyd and Conant (1990) listed Northern Black Racers (Coluber

constrictor), Eastern Milksnakes (Lampropeltis triangulum), and Kingsnakes of

both Virginia species (L. getula, L. nigra) as ophiophagus predators. Numerous

individuals are also killed each

year on Virginia's highways.

Agkistrodon contortrix is viviparous. Mating, described in Schuett and Gillingham

(1988) and

Ernst (1992), occurs in spring and fall. Gloyd and Conant (1990) noted that mating is

"frequent during the first few weeks following cessation of hibernation and occasional

throughout the active season, especially during the autumn." W. H. Martin (pers. comm.)

observed mating in Loudoun County, Virginia, on 26 May 1977 and a male "courting" a dead

(DOR) female on the Skyline Drive, Rockingham County, on 15 September 1974. C. H. Ernst

(pers. comm.) observed mating on 24 April 1985 in Fairfax County. Mating is sometimes

preceded by male combat (Mitchell, 1981a; Ernst, 1992). Gloyd (1947) recounted the following

observation made by Joseph Ackroyd

near Winchester, Frederick County, in late July 1945 (only the actual behavior is reported

here):

Possibly two-thirds of the anterior portions of the snakes' bodies were entwined

vertically

with the exception of a portion of the neck. The heads were opposite each other and were

held horizontally, three or four inches apart. They seemed to gaze hypnotically at each

other and there was a slight swaying movement between them. About one turn of coil was

wound

and unwound, first in a clockwise and then in a counterclockwise direction. At no time

did

the distance between the heads change during the rhythmic movements, and at no time did

the

snakes progress along the ground. It seemed as if the posterior ends were definitely

"anchored."

On three distinct occasions one of the snakes broke the rhythm of the dance by darting

its

head rapidly at the other. The visibility was not good but I imagined the movement to be

a

caress, with contact made somewhere in the region of the chin of the other snake.

What most amazed me was their utter disregard for me. I watched them from a distance of

about three feet, engulfed them in the rays of the light for minutes, and yet the dance

continued. From the time I first saw them until they were prodded with a stick and moved

off

into the underbrush, approximately twenty minutes elapsed.

The smallest mature male from Virginia had a SVL of 475 mm and the smallest female a SVL of

375 mm (S. J. Stahl and J. C. Mitchell, unpublished). Ovulation occurs in late May to early

June, and birth usually occurs from late August until early October. Known birth dates are

between 10 August and 6 October. W. H. Martin (pers. comm.) observed spent females and

newborn young at montane den sites in Virginia between 22 August and 22 September, and a

gravid female on 6 October. Litter size in Virginia was 3- 15 (ave. = 7.6 ± 3.9, n = 18),

but 1-21 rangewide (Ernst, 1992). Dunn (1915c) reported the first notes on reproduction in

this species in Virginia: 7 neonates born 1 September 1913 in Nelson County. Wood (1954a)

reported birth dates of 26 and 28 September and litter sizes of 6 and 7.

Eastern Copperheads appear to be more abundant in the mountains than in the Piedmont or

Coastal

Plain. Uhler et al. (1939) recorded 213 copperheads in a sample of 885 from the George

Washington National Forest. Martin (1976) reported it to be the most abundant snake that he

observed in the Blue Ridge Mountains in a 3-year period: 243 out of 545 snakes recorded.

Clifford (1976) recorded only 17 Eastern Copperheads out of 278 snakes in Amelia County in a

4-year

study. Werler and McCallion (1951) noted they were "apparently uncommon" in Princess Anne

County (= City of Virginia Beach). Quantitative studies of population size have not been

performed in Virginia. Fitch (1960) found a density of 6-9 snakes per hectare in a Kansas

population in which estimated natural longevity was 13 years and average annual adult

survivorship was 71%.

Eastern Copperheads will vibrate their tails when disturbed but will usually remain alert and

motionless, especially if found under vegetation or in other diurnal retreats (Wood, 1954a).

The characteristic alert pose at rest is with the body coiled and the head elevated at a 45°

angle. They are usually docile when caught but will strike on provocation. Very warm

Eastern Copperheads, such as those encountered on a hot summer road, are apt to be

pugnacious.

Remarks: Other common names in Virginia are highland

moccasin (Dunn, 1915a, 1918); copperhead moccasin (Dunn, 1936; Burch, 1940); moccasin

(Carroll, 1950); pilot snake, chink head, and upland moccasin (Linzey and Clifford, 1981);

and

poplar leaf (Brothers, 1992). Gloyd and Conant (1990) noted that the term "moccasin" is used

incorrectly to refer to several species of snakes, including the nonvenomous water snakes

(Nerodia), and suggested that the term not be used at all.

Agkistrodon contortrix is the least venomous of

the three venomous snakes in Virginia. As far as I can ascertain, no one in recorded

Virginia history has died from the bite of this species. A summary of snakebite patterns and

treatment is presented in the section "Venomous Snakebite."

Beck (1952) noted that a Rappahannock County myth claimed that Eastern Copperheads, like all

venomous reptiles, inflicted a wound into which they "blew" green venom from tubes. Thus,

removal of fangs would render the snake only slightly less dangerous.

Conservation and Management: Agkistrodon

contortrix

is not a species of special concern in Virginia because of its abundance and widespread

distribution. Like all snakes, Eastern Copperheads play important roles in the economy of

nature and

should be removed from human-inhabited areas, not killed. Maintenance of this species in a

natural biotic community requires an abundance of small mammal prey, open areas with hiding

places that can be used for basking, and overwintering sites that allow the snakes to

hibernate below the frost line.

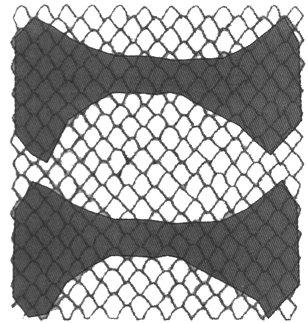

Eastern Copperheads have dark colored crossbands that are for the most

part shaped like an hourglass.

Usually some of the crossbands are broken and do not connect.

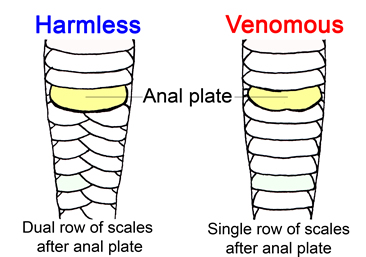

While close inspection of a snake's face and/or it's anal plate is a definitive way to distinguish a

venomous snake from a harmless species, it requires one to get dangerously close to a potentially

dangerous animal. It is far better to learn the pattern and coloration of a few snakes so that a

specimen may be identified from a safe distance.

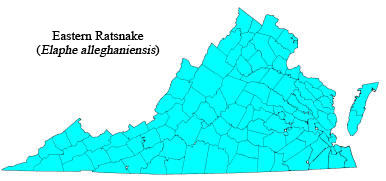

Probably the most common snake misidentified as a copperhead is the

harmless juvenile eastern ratsnake (formerly called the blackrat snake). The eastern ratsnake

starts life with a strong pattern of gray or brown blotches on a pale gray background. As the

eastern ratsnake ages the pattern fades and the snake becomes black, often with just a hint of

the juvenile pattern remaining.

Around late August to mid October depending on the temperatures, eastern

rat snakes look for a nice warm place to wait out the upcoming winter. Frequently these snake

will choose a house attic, crawlspace or basement. Luckily, copperheads don't usually seek

winter refuge in human occupied dwellings.

______________________________________________________________

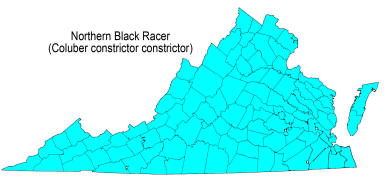

Like the Eastern Ratsnake, Black Racers are also born with a blotched

pattern. However, unlike the Eastern Ratsnake that may retain the juvenile pattern for several

years, the pattern of the Black Racer usually fades to a uniformed black within the first two

years of life. Juvenile Black Racers usually do not seek winter refuge in human occupied

dwellings. Black Racers are usually one of the first snakes to become active when spring

arrives.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

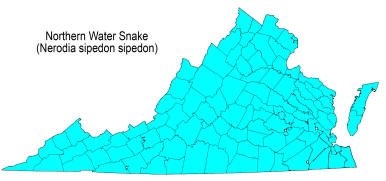

Juvenile and subadult Northern Watersnakes have a pattern that can vary

greatly in color, from dark grayish to a reddish brown. The color of some individuals

watersnakes can come close to that of some copperheads, however the pattern on the Northern

Watersnake is always narrow on the sides and wide near the backbone. This is completely opposite

of the pattern found on the Eastern Copperhead (wide on the sides and narrow near the back

bone). Some adult Northern Watersnakes retain a strong, distinct juvenile pattern while others

become a uniformed brown. As the name implies, the Northern Watersnake is usually found in close

proximity to water.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

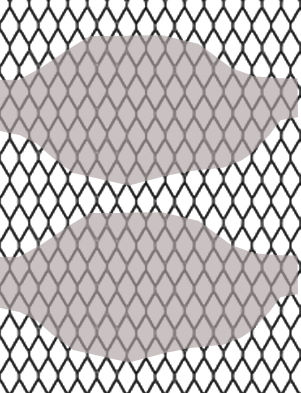

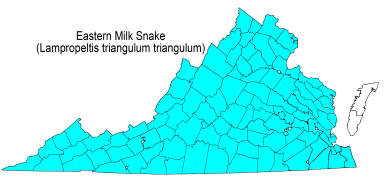

The pattern of the eastern milksnake is fairly consistent in Virginia,

however the intensity of the colors can vary quite a bit. Usually the blotches across the back

are outlined in black. Eastern Milksnakes are found statewide, but are more abundant in the

mountainous regions.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

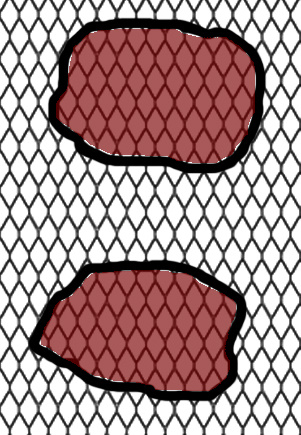

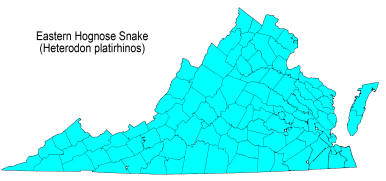

Eastern Hog-Nosed snakes are the great actors of the snake world. In an

effort to ward off predators these snakes will puff-up, hiss loudly, spread their neck and

strike with the mouth closed. If all else fails the Hog-nosed Snake will roll over and play

dead. Found statewide the pattern and coloration of these snakes can vary greatly. Eastern

Hog-noses Snakes prefer sandy soil and primarily feed on toads.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

The Red Cornsnake also known as the red ratsnake is usually more brightly

colored and and has a more reddish hue than that of the copperhead. The pattern of the Red

Cornsnake is a blotch that does not extend down the sides to the ground. Unlike the juvenile

pattern of the eastern ratsnake that fades as the snake ages, the pattern of the Red Cornsnake

remains distinct regardless of age.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

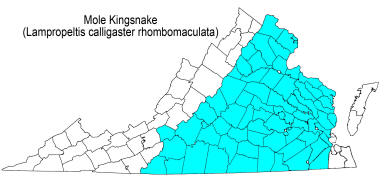

Juvenile Northern Mole Kingsnakes have a strong pattern that usually,

but not always fades to a uniformed brown as the snake ages. Northern Mole Kingsnakes are seldom

seen out in the open and are generally found under surface cover (plywood, tin, flat rocks,

etc..). Northern Mole Kingsnakes will sometime venture out in the open after a heavy rain.

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

%20_small.jpg)