Eastern Painted Turtle

Chrysemys picta picta

Common Name: |

Eastern Painted Turtle |

Scientific Name: |

Chrysemys picta picta |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Chrysemys is derived from the Greek words chrysos meaning "gold" and emys which means "freshwater tortoise". |

Species: |

picta is derived from the Latin word pictus which means "painted". |

Subspecies: |

picta is derived from the Latin word pictus which means "painted". |

Average Length: |

4.5 - 6 in. (11.5 - 15.2 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

7 in. (17.9 cm) |

Record length: |

7.2 in. (18.2 cm) |

Systematics: Originally described as Testudo picta by Johann Gottlob Schneider in 1783, who incorrectly stated its location as "Unknown, said to have been England" (Stejneger and Barbour, 1943). Schmidt (1953) restricted the type locality to New York City, but Smith and Smith (1979) noted that this was in error because Mittleman (1945a) had earlier restricted the type locality to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The collector of the Bog Turtle, Heinrich Muhlenberg, sent specimens of this species from Pennsylvania to Johann David Schoepf, who was the first to provide a detailed description of this species (Schoepff, 1792-1801). Chrysemys was first used for this species by Gray (1844). Three subspecies are recognized: C. p. picta (Schneider), C. p. bellii (Gray), and C. p. marginata Agassiz. The distributions of these subspecies were illustrated in Ernst (1971), Conant and Collins (1991), and Iverson (1992). All authors in the Virginia literature used the current nomenclature. Only C. p. picta has been documented in Virginia (see additional comments below under "Geographic Variation" and "Remarks").

Description: A moderate-sized freshwater turtle reaching a maximum carapace length (CL) of 182 mm (7.2 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia, known maximum CL is 179 mm, maximum plastron length (PL) is 171 mm, and maximum body mass is 600 g.

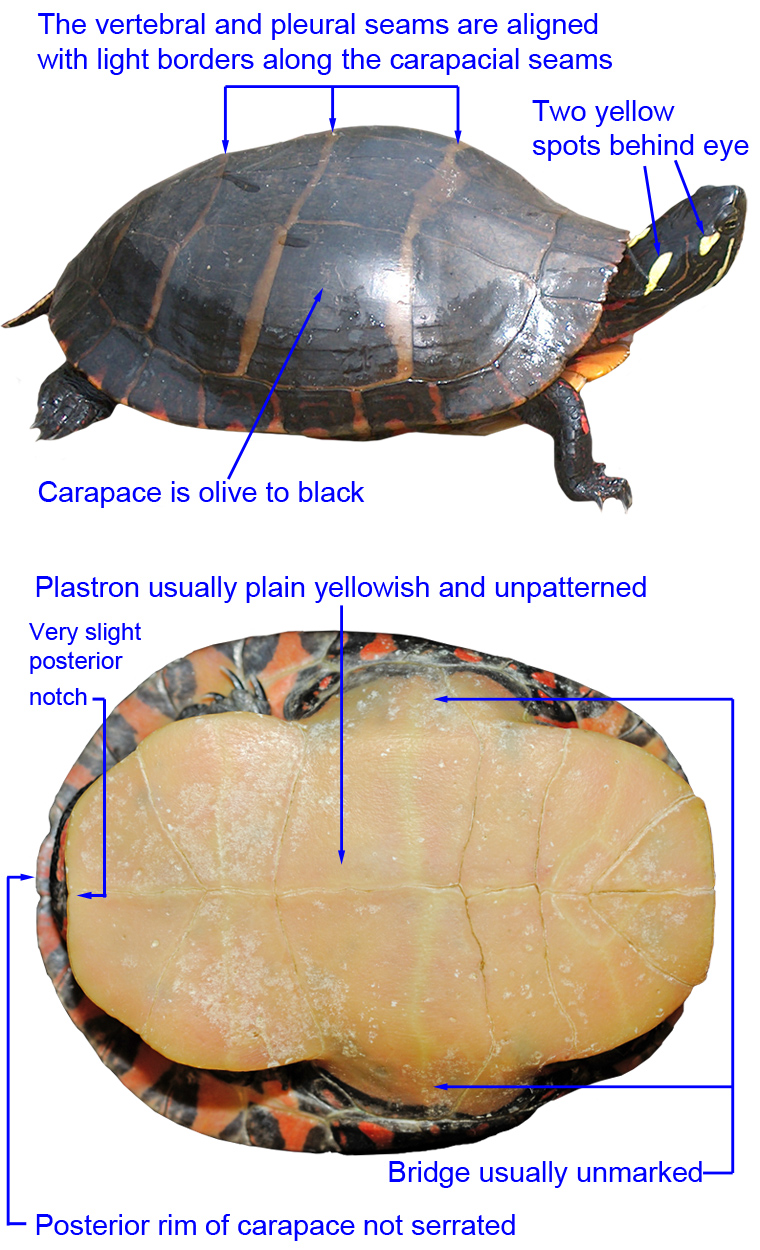

Morphology: Carapace smooth, flattened, and without serrations along posterior margin; marginals 12/12, pleurals 4/4, and vertebral scutes 5; most variation is in additional or divided vertebrals; hingeless plastron 89-96% of CL.

Coloration and Pattern: Carapace olive to dark olive brown in color; transverse seams of vertebral and pleural scutes usually aligned, seams misaligned in some individuals; seams bordered by band of yellow to yellow-orange 1-5 mm wide to form 2-3 narrow crossbands, the anteriormost one being the widest; marginals weakly patterned on carapacial side but brightly patterned with red ocelli on plastral side; some marginal pattern occurs on bridge, forming a black stripe in some turtles; plastron usually unpatterned, but some individuals have dark figures of highly variable design and size bordering midline; head black with 2 round to oval bright-yellow spots behind eyes; narrow yellow stripes on head below eyes and on chin; neck with narrow red stripes; limbs and tail dark brown to black with narrow red stripes or dashes.

Sexual Dimorphism: Adult males have elongated foreclaws (ave. = 10.7 ± 1.0 mm, 8.7-13.0, n = 35) and flattened shells. The shell of mature females is slightly domed posteriorly; they lack elongated foreclaws (ave. = 7.4 ± 0.7mm, 6.1-9.0, n = 37). Males averaged 119.9 ± 15.6 mm CL (77-162, n = 853), 111.5 ± 14.3 mm PL (72-147, n = 871), and 223.8 ± 73.1 g body mass (68-468, n = 703). Females averaged 140.0 ±12.9 mm CL (104-179, n = 357), 132.3 ± 12.8 mm PL (100-171, n = 378), and 172-600 g body mass (ave. = 372.8 ± 91.2, n = 275). Sexual dimorphism index was 0.17, The pre-cloacal distance in males was longer (4-21 mm, ave. = 13.8 ±3.1, n = 167) than in females (0-18 mm, ave. = 6.5 ± 3.5, n = 53).

Juveniles: Juveniles are patterned and colored as adults. The carapace is usually round for the first 2 years of life and elongation occurs thereafter. Hatchling Painted Turtles were 18.3-29.2 mm CL (ave. = 26.1 ± 1.7, n = 106) and 17.3-26.4 mm PL (ave. = 24.4 ± 1.4), and weighed 2.6-5.8 g (ave. = 4.6 ± 0.7).

Confusing Species: This species may be confused with other basking turtles when viewed from a distance. Pseudemys rubriventris and P. concinna lack the 2 yellow spots on the head, are usually much larger, and have high domed shells compared with Painted Turtles. Trachemys scripta scripta have distinct indentations along the posterior margin of the carapace and an elongated yellow bar on the side of the head. The introduced Red-Eared Slider (T. s. elegans) has an elongated, reddish patch behind the eye and a keeled carapace. Deirochelys reticularia has a high-domed carapace, a very long head and neck, and a single, broad yellow stripe on each foreleg.

Geographic Variation: Considerable variation exists throughout Virginia populations in the two characters that distinguish C. p. picta, the Eastern Painted Turtle, from C. p. marginata, the Midland Painted Turtle. These are the alignment of the seams on the pleural and vertebral scutes, and presence of the marginata type of figure on the plastron (see Ernst and Barbour, 1972). However, only in the upper James River drainage in Bath and Highland counties could Virginia populations be considered intergrades between the two subspecies. The olive color of these turtles is considerably lighter than elsewhere in Virginia; some individuals have complete seam misalignment and some have the plastral pattern. Intergrades may also occur in extreme northern Virginia (C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.). True C. p. marginata is found west of the Allegheny Mountains in West Virginia and northward in Pennsylvania (Conant and Collins, 1991). Dunn (1936) surmised that C. p. marginata may occur in southwestern Virginia, but the few specimens available indicate such is not the case.

The carapace of Painted Turtles inhabiting dark, blackwater, or cypress swamps, such as in Seashore State Park, is nearly black with bright yellow plastrons. Carapaces of those in other populations usually have the typical olive tinge color.

The size of adults and their growth rates depend on the type of habitat and food resources available. Considerable population variation in maximum CL occurs in Virginia. For example. maximum known CL (for females) in Laurel Lake, Henrico County, is 145 mm, but is 148 mm in Grassy Swamp Lake, Hanover County; 174 mm in Seashore State Park, Virginia Beach; and 171 mm on the Eastern Shore.

Biology: Painted Turtles occur in all manner of aquatic habitats that have permanent water. I have found them in ponds, lakes, ditches, swamps, rivers, creeks, and marshes. Preferred habitat has aquatic vegetation, soft substrate, and basking sites. Painted turtles bask frequently; they are the most common basking turtle seen in Virginia. The activity season begins with warm weather in March and continues through October, but basking turtles can also be seen on warm days in the winter months. Most (94.8%, n = 1,582) Virginia records are in April-September. Bazuin (1983) noted seasonal limits of 19 March-22 October. Body temperatures of basking turtles in late March and early April were 20.5-28.0°C (ave. = 24 ± 3.6, n = 4). Hibernation occurs in water under logs and stumps, and in muskrat and beaver lodges. Terrestrial activity occurs during nesting season (females) and when turtles seek new sources of water. Some terrestrial activity of males is unexplained.

Painted turtles are omnivores. I have recorded beetles, algae, and dead fish in Virginia individuals. Ernst and Barbour (1972) recorded animal prey (invertebrates and fish) in 64% and plants in 100% of individuals in a sample from Pennsylvania. Eggs of painted turtles in nests are eaten by raccoons (Procyon lotor), skunks (Mephitis, Spilogale), foxes (Urocyon, Vulpes), and small mammals who eat them singly underground (J. D. Congdon, pers. comm.). Juveniles in Virginia have been eaten by largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), Eastern Snapping Turtles (Chelydra serpentina), herons (Ardea, Butorides), crows (Corvus spp.), and raccoons. Raccoons often eat the limbs and head of these turtles before scooping out the organs with their long foreclaws. Considerable annual mortality of terrestrial individuals is caused by vehicular traffic. On golf courses, females seeking or returning from nesting sites are killed by grass mowers (Mitchell, 1988).

Virginia Painted Turtles lay one to two clutches annually, although some females may not produce a clutch in some years. Three clutches in a single season have not been documented. Clutch size for a sample of females obtained from throughout Virginia was 3-9 eggs (ave. =5.7 ± 1.6, n = 32). Average clutch sizes of 4.2 (1-9, Hanover County population) and 4.1 (3-6, Henrico County population) have been reported (Mitchell, 1985c, 1988, respectively). Clutch size in northern Virginia averaged 5.1 (4-11; C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.). Mating occurs in water and has been observed March-June and on 3 October. I have described the male reproductive cycle (Mitchell, 1985a) and the female cycle (1985c) for a Hanover County population. Nesting dates in Henrico County were 30 May to 13 July (Mitchell, 1988). Known nesting dates in northern Virginia are 27 May to 4 July (C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.). Richmond (1945b) reported nesting dates of 16 May-1 July in New Kent County. The smallest mature male I measured was 72 mm PL and the smallest mature female was 100 mm PL. In an urban lake in Henrico County, males matured at 71 mm PL and females at 97 mm (Mitchell, 1988). Males in this population matured at age 4 and females at ages 6-8 (Mitchell, 1988). Eggs from females throughout the state averaged 30.3 ± 1.3 x 17.4 ± 0.9 mm (length 27.4-32.8; width 15.2-19.0 mm, based on means of 28 clutches) and weighed an average of 5.5 ± 0.7g(3.7-6.9, based on means of 29 clutches). Laboratory incubation time was 62-76 days (ave. = 67 ± 4, means for 18 clutches). Hatching dates were 2-23 August. In the field, hatchlings overwinter in the nest and emerge in March and April (Mitchell, 1988).

The population of one Henrico County population was estimated to contain 517 ± 17 Painted Turtles (Mitchell, 1988). It consisted of 30.4% adult females, 35.2% adult males, 7.7% immature females, and 26.7% unsexed juveniles. Considerable variation exists, however, in the structure of other Virginia populations. Adults in this population had a 94-96% chance of surviving from one year to the next, whereas survivorship of juveniles was 46%. Painted Turtles in Michigan are known to live over 30 years (Gibbons, 1987).

Painted Turtles are active during the day and bask frequently, most often between the hours of 0800 and 1300 (Lovich, 1988; J. C. Mitchell, unpublished). Aggressive behaviors observed by Lovich (1988) at Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge during basking included open mouth gestures, biting, pushing, lateral displacement, and vertical displacement. The number of aggressive acts increased with water temperature. Males move more frequently than females early and late in a year's activity season, whereas females move more frequently and over longer distances during the nesting season.

Remarks: The name "skilpot" is often used for this species in Virginia (Dunn, 1915a, 1918, 1936; Hoffman, 1949b; Carroll, 1950). The name is derived from the Dutch word schildpad, meaning "tortoise or sea turtle" (sch is pronounced as sk).

Geographic variation needs to be examined to determine the patterns of intergradation of C. c. picta and C. p. marginata in Virginia. True marginata has not been documented for Virginia, and it is for this reason that I have not considered it a part of the Commonwealth's turtle fauna.

Abnormal Painted Turtles are occasionally found. For example, a two-headed hatchling was found in Chesterfield County in April 1973, a large male with a cleft palate was found in Prince Edward County in July 1981, and a male with a kyphotic (deformed vertebral column) carapace was found in Henrico County in May 1980.

It is against federal law to sell a turtle under 5 inches (12.7 cm) in shell length unless certified free of Salmonella bacteria, which causes salmonellosis, a human gastrointestinal disease. Turtles not native to Virginia should not be released. Mitchell and McAvoy (1990) found no Salmonella in 100 wild individuals in Virginia, but did isolate three samples of the closely related Arizona serotype of bacteria.

Conservation and Management: Painted Turtles are adapted to a wide variety of natural and human-altered habitats (Mitchell, 1988). Consequently, it is an abundant turtle throughout most of Virginia and requires little active management outside of protection of all wetlands. Two illegal activities cause an unknown amount of mortality each year: fishing traps set in deep water, causing drowning, and the shooting of basking turtles for "sport." Collecting for the pet trade has had an unknown effect on Virginia populations. It is now against Virginia law to buy or sell this or any other native species.

References for Life History

Identification Characteristics:

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Albemarle

Alleghany

Amelia

Amherst

Appomattox

Arlington

Augusta

Bath

Bedford

Botetourt

Brunswick

Buchanan

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Carroll

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Clarke

Culpeper

Cumberland

Dinwiddie

Essex

Fairfax

Fauquier

Fluvanna

Franklin

Frederick

Giles

Gloucester

Goochland

Greene

Greensville

Halifax

Hanover

Henrico

Henry

Highland

Isle of Wight

James City

King George

King William

Lancaster

Loudoun

Louisa

Lunenburg

Madison

Mathews

Mecklenburg

Middlesex

Montgomery

Nelson

New Kent

Northampton

Northumberland

Nottoway

Orange

Page

Patrick

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Pulaski

Rappahannock

Richmond

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Rockingham

Scott

Shenandoah

Smyth

Southampton

Spotsylvania

Stafford

Surry

Sussex

Tazewell

Warren

Westmoreland

Wythe

York

CITIES

Alexandria

Chesapeake

Hampton

Lynchburg

Manassas

Manassas Park

Newport News

Norfolk

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Waynesboro

Williamsburg

Verified in 85 counties and 12 cities.

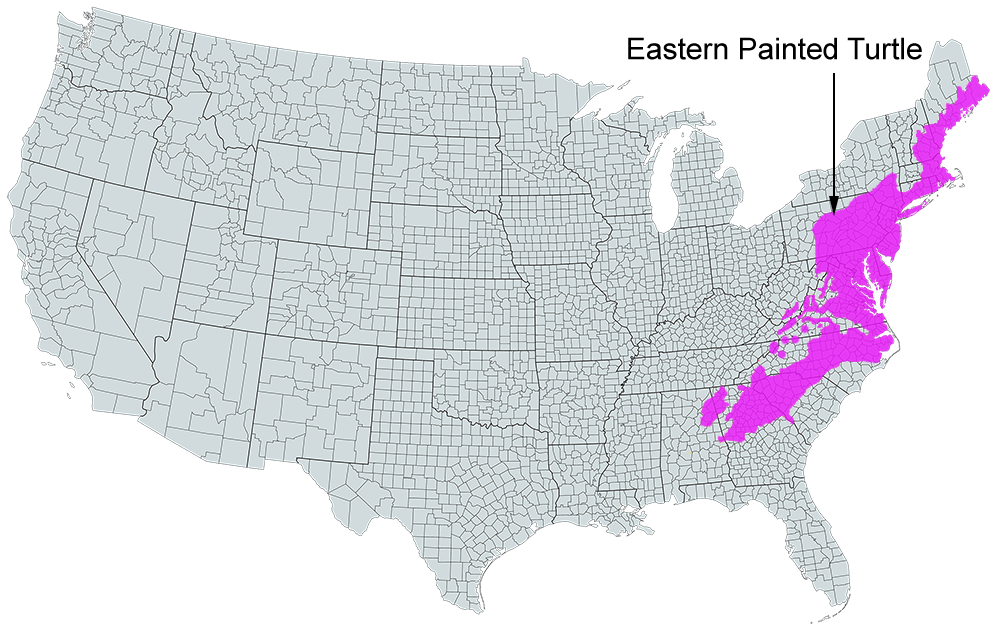

U.S. Range