Northern Red-bellied Cooter

Pseudemys rubriventris

Common Name: |

Northern Red-bellied Cooter |

Scientific Name: |

Pseudemys rubriventris |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Pseudemys is derived from the Greek word pseudes which means "false" and emys which means "turtle". |

Species: |

rubriventris is derived from the Latin word ruber meaning "red" and venter meaning "belly" (plastron). |

Average Length: |

10 - 12.5 in. (25.4 - 32 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

13.1 in. (33.4 cm) |

Record length: |

15.8 in. (40 cm) |

Systematics: Originally described as Testudo rubriventris by john LeConte in 1829 from a specimen collected near Trenton, New Jersey. The genus Pseudemys was first used for this species by Lonnberg (1894). Other names previously applied to this species in the Virginia literature are Emys rubriventris and Ptychemys rugosa (Agassiz, 1857) and Pseudemys rugosa (Smith, 1904). Numerous authors followed McDowell (1964) and used Chrysemys rubriventris (e.g., Ernst and Barbour, 1972; Hardy, 1972; Musick, 1972; Conant, 1975; Mitchell, 1974a, 1976a, 1981a; Delzell, 1979; Tobey, 1985). Spinks et al. (2013, Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 68: 269–281) examined variation in mitochondrial and nuclear DNA across all recognized taxa of Pseudemys, and revealed almost no support for the currently recognized species groups, species, or subspecies. They concluded that the genus was probably over-split, but offered no explicit taxonomic suggestions. Pending more extensive genetic sampling and phylogenetic analyses, and in the interest of stability, we continue to follow the content recommended by Seidel (1994, Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 1: 117–130). No subspecies are recognized.

Description: A large freshwater turtle reaching a maximum carapace length (CL) of 400 mm (15.7 inches) (Ernst and Barbour, 1972). In Virginia, known maximum CL is 334 mm, maximum plastron length (PL) is 326 mm, and maximum body mass is 3,900 g.

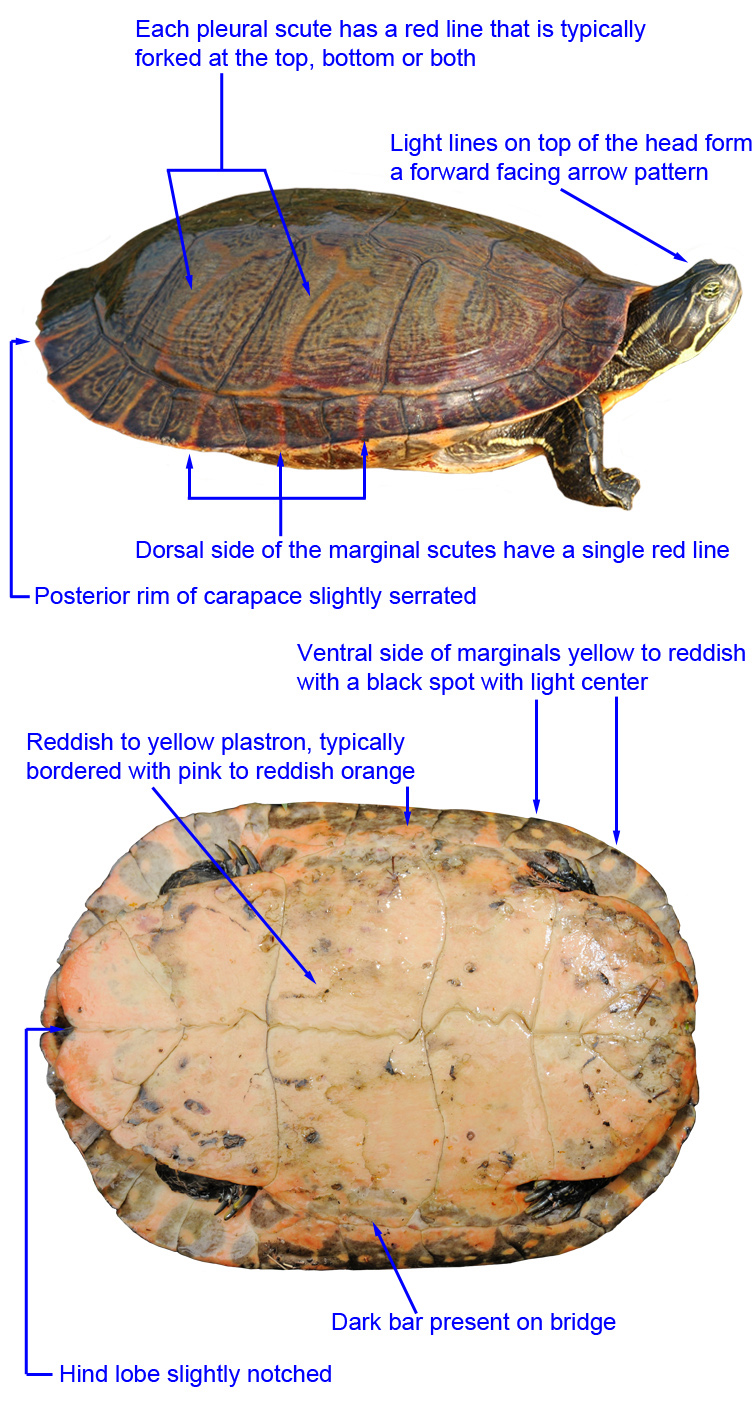

Morphology: Carapace elongated, somewhat flattened, slightly serrated posteriorly, and rugose in adults; usually marginals 11/11, pleurals 4/4, and vertebrals 5; hingeless plastron 88-98% of CL.

Native Pseudemys Face Comparisons

|

|

|

| Eastern River Cooter Pseudemys concinna concinna |

Coastal Plain Cooter Pseudemys concinna floridana |

Northern Red-bellied Cooter Pseudemys rubriventris |

Coloration and Pattern: Carapace olive-brown to nearly black; each pleural scute with a vertical red line that is often forked at upper and/or lower ends; single red streak present on dorsum of each marginal scute; carapacial pattern in old males breaks up to form a highly variable mottling of dark olive, yellow, and red; a few individual females nearly all black; ventral surfaces of each marginal yellow to reddish with black spots; bridge with several black spots or a black bar; plastron reddish to yellowish, almost always bordered with pink or reddish orange; dark pattern that occurs along seams in juveniles and immatures fades with age; skin on head, neck, and limbs black with narrow yellow stripes; prominent middorsal streak on dorsum of head joins thin lines above eyes at snout to form prefrontal arrow characteristic of this turtle; tip of upper jaw notched with a toothlike cusp on either side.

Sexual Dimorphism: Adult females are larger than males. Females averaged 285.7 ± 18.4 mm CL (258-334, " = 53), 269.0 ± 17.7 mm PL (242- 326, n = 62), and 2,787.6 ± 446.4 g body mass (1,920-3,900, n = 51). Adult males averaged 230.9 ± 32.5 mm CL (179-295, n = 34), 204.5 ± 29.3 mm PL (160-273, n = 39), and 1,400.0 ± 622.1 g body mass (650-2,867, n = 29). Sexual dimorphism index was 0.24. The foreclaws were elongated in males (ave. = 20.5 ± 2.6 mm, 15.6-23.6, n = 12) and the anal opening extended beyond the posterior margin of the carapace. Foreclaw length in females was 9.0-14.1 mm (ave. = 11.5 ± 1.5, n = 12); the anal opening did not extend beyond the carapacial margin. Precloacal distance in males was 27-57 mm (ave. = 42.3 ± 8.4, n = 14) and in females was 4-25 mm (ave. = 14.9 ± 6.9, n = 19).

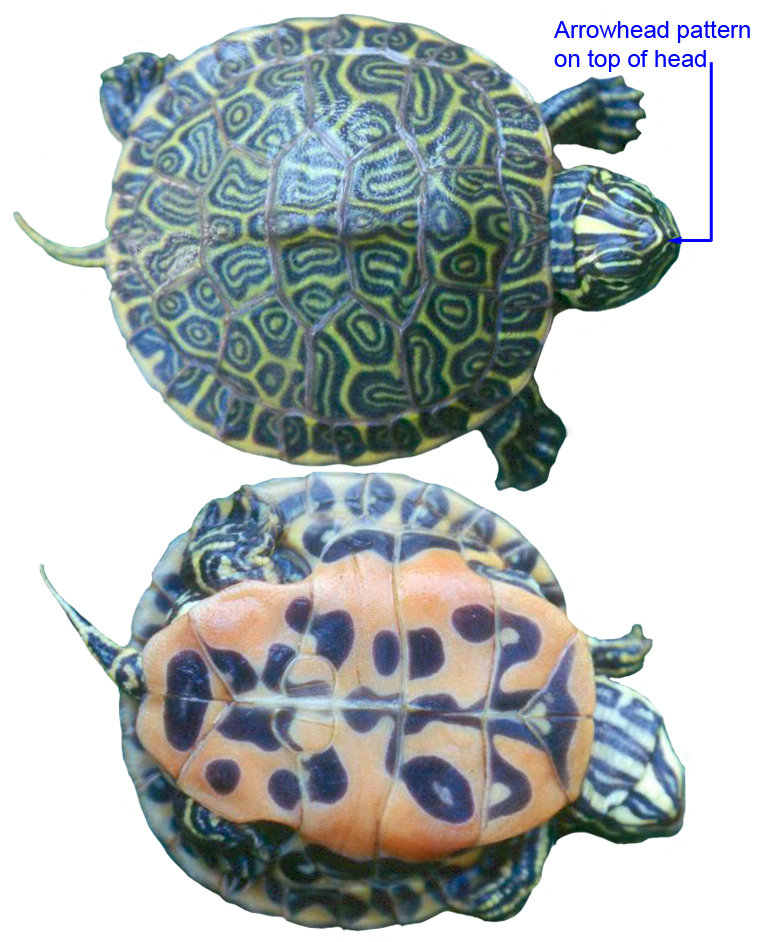

Juveniles: At hatching, the carapace is green and the vertical lines on the pleural scutes are yellow. The plastron is red to yellow (18.4% red, 73.5% yellow, and 8.2% orange, n = 49) and bears an irregular black figure that followed the seams of the plastral scutes. This figure consists of asymmetrically placed spots and broad bands along the seams. The figure fades with age and the yellow markings on the carapace change to red. The skin is greenish, and the lines on the neck and legs are greenish yellow. The upper jaw has a notch at the midline between two weak cusps. Hatchlings from Virginia were 24.0-37.3 mm CL (ave. = 31.3 ± 3.0, n = 158) and 23.3-35.8 mm PL (ave. = 30.0 ± 2.8), and weighed 5.6-12.2 g (ave. = 8.8 ± 2.0). N. D. Richmond (pers. comm.) found 12 hatchlings in April 1955 that weighed 7.8-9.4 g (ave. - 8.8 ± 0.6).

Confusing Species: Pseudemys rubriventris may be confused with P. concinna, which has a backwards "C" in the 2d pleural scute, a yellowish plastron, and no prominent cusps on the upper jaw. Pseudemys c. floridana has light yellow lines on the carapace, a yellowish plastron without markings, and lacks the medial notch and cusps on the upper jaw. These species lack the prefrontal arrow. Chrysemys picta has transverse olive-yellow lines across the carapace along the pleural and vertebral seams and 2 yellow spots behind the eye on each side of the head.

Geographic Variation: There is no apparent geographic variation in morphology, color, or pattern in Virginia populations. Northern Red-bellied Cooter in areas north of Virginia are darker and apparently become melanistic with age (Ernst and Barbour, 1972). Very black or melanistic individuals have not been found in Virginia. Some individuals from parts of southeastern Virginia have weak cusps or lack them altogether, and have carapacial patterns suggestive of P. floridana. These may be possible hybrids, as suggested by Crenshaw (1965) and Seidel and Palmer (1991).

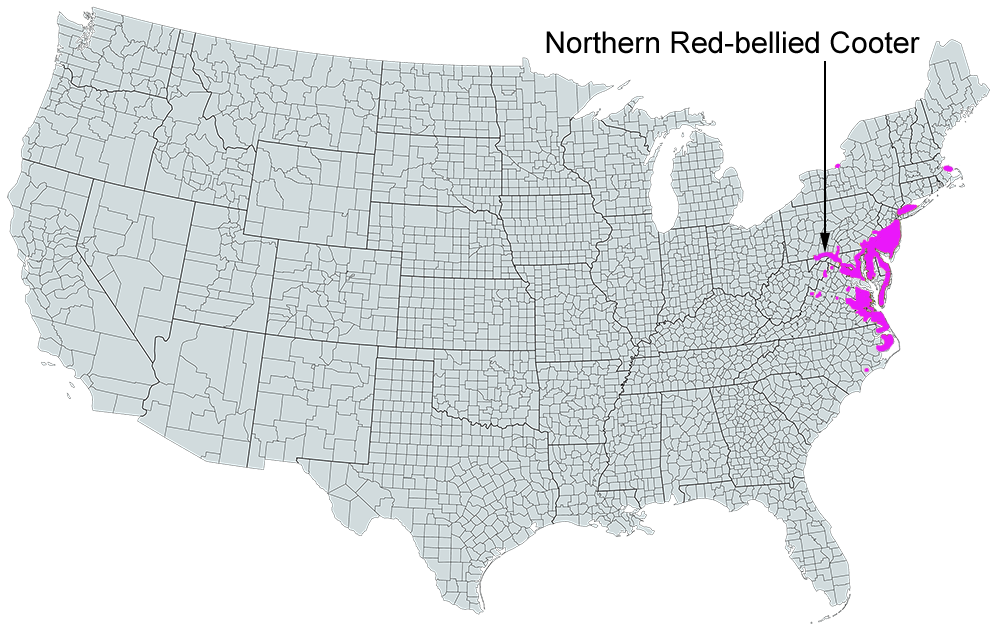

Biology: This is primarily a turtle of freshwater lakes, ponds, and blackwater swamps in the Coastal Plain and on the Eastern Shore. Slow-moving creeks are also inhabited, as are large rivers, including the James, Rappahannock, Potomac, and North and South Forks of the Shenandoah. Northern Red-bellied Cooters occur in brackish water habitats, as evidenced by the occurrence of barnacles on their shells. One male caught in Suffolk had 24 barnacles attached to the carapace and bridge. Preferred habitat includes emergent and submerged freshwater plants, basking sites near deep water, and a soft substrate for overwintering. The activity season begins with warm weather in March but basking activity occurs in any warm period in winter. This turtle has been caught from March to December, but most records (96.4% of 346) are March through October. Pseudemys rubriventris overwinters in the soft substrate in channels of ponds, lakes, and rivers. Substantial terrestrial activity occurs during nesting season.

Northern Red-bellied Cooters are herbivorous as adults but omnivorous as juveniles, although C. H. Ernst (pers. comm.) noted that captive males eat more animal food than females. Plant remains (leaves and stems) have been found in all the feces examined. I have observed P. rubriventris eating leaves of water-lily (Nymphaea odorata) and pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata). One captive juvenile ate mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis) but could not distinguish between chunks of fish and similar-sized and -colored pebbles until they were bitten. Predators of adults include raccoons (Procyon lotor) and humans, who kill them by shooting, smashing them with cars, and mutilating them with large grass mowers. Juveniles are eaten by large wading birds, Snapping Turtles (Chelydra serpentina), raccoons, and largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Eggs are consumed by raccoons and skunks (Mephitis mephitis) (N. D. Richmond, pers. comm.). Smith (1904) observed a crow (Corvus spp.) along the lower Potomac River waiting until a female finished nesting before digging up and eating two eggs. Schwab (1989) found the remains of a hatchling in a white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) nest under a piece of plywood in the Dismal Swamp.

Pseudemys rubriventris females in Virginia lay up to two clutches of eggs per year based on the presence of enlarged follicles with oviductal eggs in several individuals. I have observed mating activities in April, May, and June. The smallest mature female from Virginia measured 242 mm PL and the smallest male 160 mm PL. Known nesting dates are between 18 May and 11 July, with most occurring in June. Richmond (1945b) reported nesting dates of 18 May to 4 July in New Kent County and C. H. Ernst (pers. comm.) recorded dates of 25 May to 4 July in Fairfax County. Nests are dug in sandy soils up to several hundred meters from water during the day or night, although the former is most common. The nest is an ovalshaped cavity dug to about 10 cm deep, 11-12 cm wide in the chamber, and 7-8 cm wide at the entrance. Clutch size averaged 14.8 ± 4.7 eggs (8-29, n = 18). Richmond and Goin (1938) and N. D. Richmond (pers. comm.) found clutches of 9 to 13 eggs (ave. = 11.0 ± 1.5, n = 6) in New Kent County during 1938-1942. C. H. Ernst (pers. comm.) noted clutches of 8-12 (ave. = 9.8, n = 8) at Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge. Smith (1904) reported clutches of 9-35 eggs from the Potomac River area. Eggs from Virginia females averaged 35.2 ± 2.6 x 23.8 ± 1.6 mm in size (length 29.8- 39.8, width 19.7-26.0, n = 265) and weighed 6.8-14.0 g (ave. = 11.6 ± 2.1). Laboratory incubation time was 62-76 days (ave. = 71.5 ± 4.1, n = 16 clutches). Hatching occurred from 4 August to 21 September. Hatchlings overwinter in the nest and emerge in the spring. N. D. Richmond (pers. comm.) plowed up a nest in a New Kent County garden on 22 August 1942 and found hatchlings with their egg shells. Mitchell (1974a) reported a nest with emerging hatchlings on 13 April and Smith (1904) reported one on 10 April. N. D. Richmond (pers. comm.) plowed up nests in fields on 24 March and 1 April and found single hatchlings on 25 April and 3 May. The turtles found on 1 April were "stacked on top of each other but oriented so that each was upright."

Little information is available on the population ecology of this species (Graham, 1991). Sexual dimorphism has been reported for turtles from throughout the range (SDI = 0.10; Iverson and Graham, 1990), from Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Virginia Beach, Virginia (0.23; Mitchell and Pague, 1991a), and from throughout Virginia (0.24; see above). In Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge, P. rubriventris occurs in microsympatry with Clemmys guttata, Chelydra serpentina, Chrysemys picta, Kinosternon subrubrum, and Trachemys scripta (Mitchell and Pague, 1991a).

Northern Red-bellied Cooters are active during the day and bask frequently. Aggressive behavior between these turtles has not been reported, but Lovich (1988) observed two instances of P. rubriventris displacing Chrysemys picta from their basking sites on logs.

In his historical volume on comparative embryology, Louis Agassiz (1857) provided information on several aspects of the biology of this species, in part based on Virginia turtles. He reported data on heartbeat, length of digestive tract, lung capacity, descriptions of juveniles and adults, and information on harvesting for food, and provided color illustrations of all size classes. Ernst and Norris (1978) reported on the occurrence of the alga Basicladia crassa on the carapace of an adult female they found near Williamsburg. Mitchell and McAvoy (1990) found no Salmonella bacteria in seven Northern Red-bellied Cooters from three natural populations in Virginia.

Remarks: Other common names for this species are yellow-bellied terrapin, slider, terrapin, and fresh-water pullet (Hay, 1902; Smith, 1904, Dunn, 1918); and red-bellied terrapin (Hoffman, 1949b).

Specimens of Pseudemys rubriventris were sold in the Washington and Philadelphia markets in the 1800s (Agassiz, 1857; Smith, 1904).

On one day in December, about the year 1883, 240 terrapin were there caught at one seine haul by Mr. L. G. Harron, now of the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries; they had been buried on a shallow bar, but had uncovered themselves under the influence of an unusually warm spell. The largest were sold for seventy-five cents apiece in Washington, which was about the average price in those days, while the smallest, six to seven inches long, were worth only fifteen or twenty cents. (Smith, 1904)

Conservation and Management: Northern Red-bellied Cooters are not considered species of special concern in Virginia at this time. Areas of concern are harvesting for commercial purposes and loss of wetland habitat. Information on harvest rates and effects on populations are needed to determine if active management is needed. Urban development around ponds and lakes destroys nesting sites and negatively impacts emergent aquatic vegetation on which these turtles feed. Two locations where P. rubriventris populations have been impacted by these problems are Laurel Lake, Henrico County, and Lake Smith in Norfolk and Virginia Beach. Proper management by local citizens and planning commissions could help secure the long-term future of this visible component of Virginia's natural heritage. Shooting of basking turtles should be illegal everywhere.

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

The ontogenetic shift in pigmentation (reticulated melanism) of Northern Red-bellied Cooters can produce some beautiful and unusual patterns.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Arlington

Augusta

Campbell

Caroline

Charles City

Chesterfield

Clarke

Essex

Fairfax

Fauquier

Fluvanna

Frederick

Gloucester

Goochland

Greene

Hanover

Henrico

Isle of Wight

James City

King and Queen

King George

King William

Lancaster

Loudoun

Middlesex

New Kent

Northampton

Northumberland

Nottoway

Orange

Page

Prince George

Prince William

Richmond

Shenandoah

Southampton

Spotsylvania

Surry

Sussex

Warren

Westmoreland

York

CITIES

Chesapeake

Hampton

Hopewell

Newport News

Norfolk

Richmond

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Waynesboro

Verified in 43 counties and 9 cities.

U.S. Range

306 2-sm.jpg)

309 2-sm.jpg)